From the Exhibition:

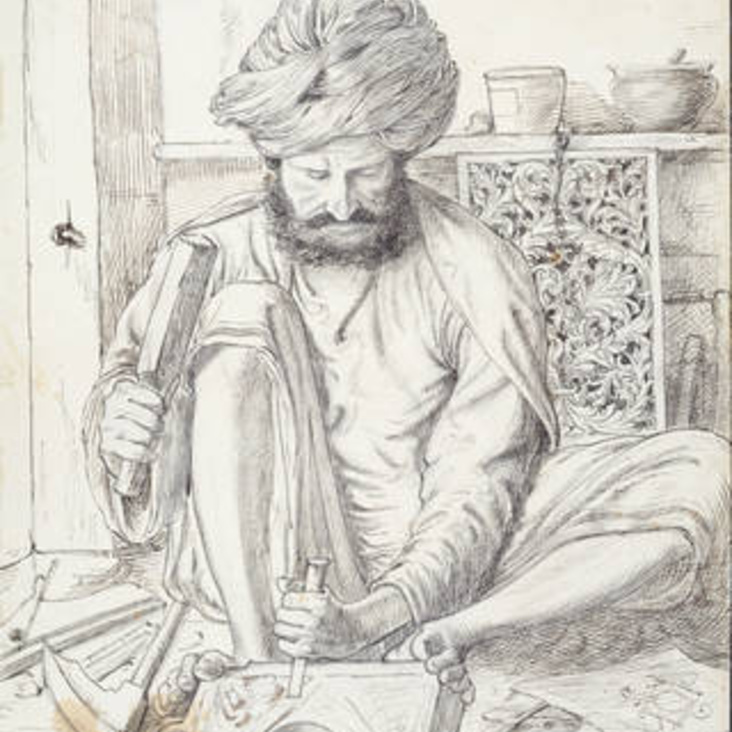

John Lockwood Kipling: Arts & Crafts in the Punjab and London

September 15, 2017–January 7, 2018

This article was originally created by the Victoria and

Albert Museum for the exhibition which took place at the Museum, January 14 – April 2, 2017.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

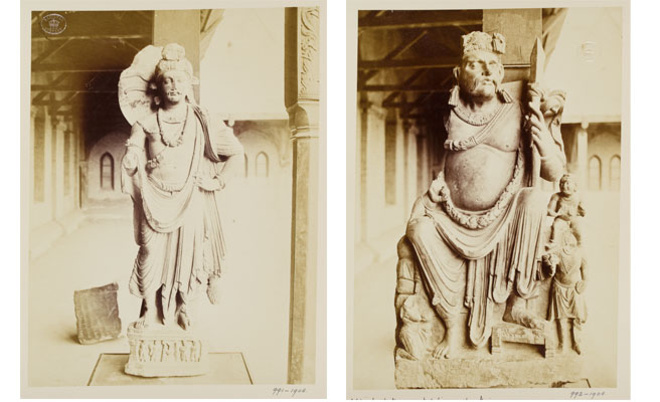

John Lockwood Kipling spent 18 years as chief curator of the Lahore Museum in Pakistan. During this time, Kipling developed a fascination for the collection and curation of Buddhist antiquities from the Gandhara (now Peshawar) region of Pakistan, which he described as, “unique in interest and beauty of workmanship.”

Lahore Museum’s collection of Gandharan Buddhist sculptures is now recognized as a unique world collection with one of its most famous objects, The Fasting Buddha, included on the Unesco World Heritage list.

The opening chapter of the novel Kim, written by Kipling’s son Rudyard, brings their original display to life:

There were hundreds of pieces, friezes of figures in relief, fragments of statues and slabs crowded with figures that had encrusted the brick walls of the Buddhist stupas and viharas of the North Country and now, dug up and labelled, made the pride of the Museum.

—Rudyard Kipling, extract from Kim

The excitement, frustration, and competitive aspect of assembling these collections is evident in Kipling’s annual reports for the museum. In 1884 – 85 he described a Gandharan sculpted panel from the Yusafzai valley, presented by Mr. Dempster, as “the most perfect in preservation and the most elaborate and skillful in execution of all the objects in the museum”. Some years earlier, in his annual report from 1879 – 80, he expressed his frustration that the South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum) did not appear to share his view, possibly due to their focus at that time on the Arts and Crafts movement. When Kipling showed them photographs of the collection, they merely responded that they would “probably” send for casts at a later date for the India Museum, whose collections had recently transferred to South Kensington. Casts of the Gandharan Buddhist sculptures were eventually sent to the Victoria and Albert Museum and are still held in the collections today, whilst the originals remain on display at the Lahore Museum.

The same year Kipling had joined forces with Mr. W. Simpson, the proprietor of and special artistic correspondent to the Illustrated London News. Commenting in his annual report, Kipling noted that Simpson had also taken up the subject of the ‘archaeology of the frontier’ in a letter to the Times newspaper (London), insisting on the importance of the sculptures, and that they should be molded and made more extensively known.

Kipling’s final annual museum report of 1892 – 93 mentions detailed instructions left with the Public Works Department, which was administered by the British Administration, for the appropriate display of Buddhist antiquities in the museum. In his previous report of 1888 – 89, Kipling noted that, “the lists and numbers of the articles in the various cases have been completed and it would be possible to print them as a catalogue. ” This catalogue is the only one which Kipling himself produced.

The period of Kipling’s curatorship of the Lahore Museum is marked by frequent exchanges of materials between museums in India and elsewhere. In seeking to build, understand, and preserve this collection, Kipling’s persistent lobbying for keeping the collection together and for the systematic and specialist study of its individual pieces contributed significantly to its creation and continued existence.